In this article (with podcast) we discuss the basics of training with power right through to the physiological benefits any regular athlete can obtain by effectively training with a power meter. We also outline the common mistakes people make with their cycling training (including power vs. heart rate) and break down the technical aspects to training with power, such as normalised power, training zones. Lastly we explain the functional threshold power (FTP) test.

But firstly, who is Harry Hanley? Or better yet: why do we have him on the home of the big podcast to talk about power training?

Well, for starters, he knows how to win a bike race.

At 52 years of age, you’ll see Harry down at the local criteriums, putting many young men to the sword in A grade.

He often gets podiums, has won national masters titles, and recently (in the weekend that’s just gone) took out the state Masters criterium championships.

While Harry will tell you in this podcast that training with power is only one part of a winning formula – and we agree – you can’t deny his meticulous training regime that is centred around a power meter.

With a PhD (Doctor of Philosophy, Geomatics) and a Bachelor of Engineering, you could say his brain is rather technical. After training with power for a number of years, Harry actually built his very own power software and became a cycle coach.

Listen to the podcast here:

Podcast (podcast-the-hollywood-hour): Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | Email | RSS

How does a power meter on a bike work

Firstly, there are a number of main stream brands that offer power meters for bikes. Stages is an entry level and the benchmark would be SRM.

The SRM unit is considered the benchmark because of its consistency in delivering reliable power data for an athlete to work with. SRM can do this because their power meters have been built with their own German manufactured equipment and contain more strain gauges than other power meters on the market.

So how does it work?

By measuring the force applied to either a pedal, spider or crank arm, the strain gauges within the device convert the output into power/watts. Also taken into consideration is rotations of the pedal or crank arm, with the power output ultimately delivered to your computer system on-bike.

The challenge that comes with this process is delivering consistent and reliable power to your computer. Weather, device age, and battery life are just a few variables that can throw power out.

When power is not working correctly on your bike, it can become a major hindrance to the efficiency of your training regime. Hence, many athletes looking to get the most of their training will turn to SRM.

Why train with a power meter (vs. a heart rate monitor)

Heart rate will typically increase during a long steady ride and can fluctuate depending on your fitness level and how you feel on any given day. It’s not a consistent measurement for zone training in comparison to power output.

Harry Hanley likes to call a power meter a “tool”. A tool that provides a more reliable and analytical way to approach your training.

The analogy Harry uses is running.

If you’re a runner and you go out for a 2.5 or 10 km run, chances are you’re going to keep a steady pace.

If you’re training for an event you might pick up the pace from time to time, but your efforts will be well executed based off guidance you’re obtaining from a program.

When you give someone wheels there’s this disconnect that happens.

For example, tell someone to go out for a 1-2 hour tempo ride, and they’ll more than likely mess it up, according to Harry.

People see other riders go past and they will jump on a wheel.

There may be a small hill to climb and the human instinct is to go harder up the hill and roll down it without pedalling

The end result is a lot of inconsistencies in the training ride that doesn’t attribute to an effective way of building your base fitness nor your threshold capacity.

The power meter acts as a tool, providing analytical data on your output, and thus, insight into an intensity level. Once you know your intensity you can train with proven structure and methods that have been demonstrated to drastically improve rider performance.

Check out this podcast: Training with Structure.

What are training zones (including FTP test)

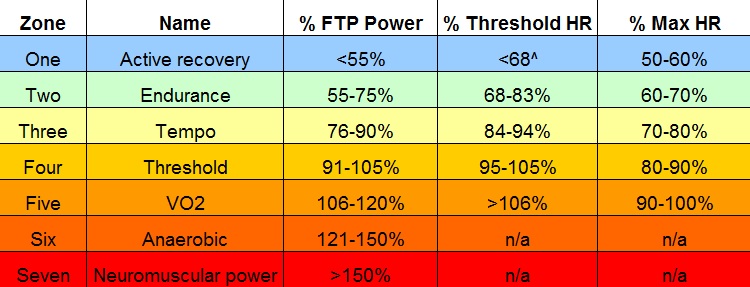

Training zones are split across 7 different pillars, as outlined in the below table. These zones – from recovery to neuromuscular – are based on fundamental physiological principles that enable athletes to effectively build base and improve anaerobic and neuromuscular output.

The benefit of having a power meter is that you can accurately train within specific zones.

Heart rate is another common mechanism used to train within these seven zones, however, the issue with heart rate is that over the course of a ride/workout an athlete’s heart rate may rise due to fatigue. A rising heart rate will essentially alter your zones during an activity and train the body to produce less output the longer the activity is. It’s like watching your training fall off a cliff.

In order to obtain your power zones you can either go to a V02 max test or a more simple way is a field based step test.

A step test is run on an indoor trainer where an athlete will warm up for 10 minutes. You would start out a moderate rate, like 150 watts. Following the 10 minute warm-up, every 90 seconds the trainer will increase output by 20 watts. A comfortable cadence of 95 -100 rpm is required until you basically can’t pedal anymore.

It’s all over and done within around 20 minutes (including the warm-up).

Whatever number you hit in the indoor trainer for the last 90 seconds is the number you use to provide a formula to get your functional threshold power (FTP).

For example, in a test that I completed in February 2017, I hit a final number of 421 watts in the ramp test. From this number my estimated FTP was 347 watts. Then my zones could be understood more clearly.

What is the sweet spot for training with power?

Harry makes an interesting comment in the podcast.

Many of the athletes he has seen come through the Hurtbox coaching program can get around fast bunch rides but can’t sit on 185 watts on an indoor trainer for one hour without their heart rate going through the roof.

These same athletes can run high intensity efforts sporadically over the course of 30-45 minutes. However, what they would find with this type of training is periods – perhaps weeks in length – where they feel fatigued. They would also be highly unlikely to have a proper chance at winning a bike race.

Why?

They have no foundation to work with (aka base fitness).

While some may challenge the “sweet spot” for training, a great starting point for cyclists looking to take their performance to the next level would be building the base.

The benefits of a power meter is that once you’ve determined your training zones you can ride consistently without falling out of your most effective zone, being zone two for base training.

For me, if I sit between 191 and 260 watts, that is my sweet spot. I tend to stay at the higher end of that number when training, but ultimately I’m being dictated by power numbers on the screen, as opposed to a heart rate that can fluctuate depending on your physiological state or how you’re feeling that day.

Average Power vs. Normalised Power

Normalised power is a commonly discussed attribute of power meter training but often misunderstood.

The best way to describe normalised power is to consider the differences between a fast bunch ride vs. a cruise along the beach.

If you go out and hold 220 watts for your cruise you’ll get to the café feeling fresh and ready for the day.

If you go out on a fast bunch ride, you power may jump between 10 watts to 400 watts and you’ll get to the café feeling stuffed, ready for a sleep.

Interestingly, your average power for these rides could be exactly the same i.e. 220 watts. Yet one ride leaves you feeling good and the other cooked.

Normalised power takes into consideration the “stress” factors that come into play when riding outdoors – fast bunches, hill climbs, windy conditions – which create a more physiologically demanding environment.

Understanding Normalised Power means athletes can train more effectively by understanding the stress levels of each ride and not overcooking themselves.

Reactive training vs. proactive training

In the podcast, Harry talks about the power meter making cyclists more proactive with their training.

This is because they’ve been empowered – assuming they’ve spoken with a coach – with an understanding of what to do.

Before intimately understanding power and power zone training, many cyclists will hit up the local bunch ride as their core activity. There, you’re reacting to the wheels of others and following the moves.

One minute your freewheeling and the next you’re pushing 400 watts. However, never will you really push yourself beyond a certain limit, as you don’t want to get dropped!

As discussed above, steady tempo riding is a great way to build the base, but what about race specificity?

Harry talks about the benefits of hill repeats: training the lactic system proactively via multiple 1 -2 minute efforts above threshold. You would simply never do this on a bunch ride, because you’d get dropped, and thus, you’re never really training the lactic system effectively.

Hill repeats give the muscles an understanding of how to deal more effectively with lactic acid. Within effort training you’re essentially pouring lactic into the muscle during the effort period and then during a 2-3 minute recovery the lactic is flooding back out of the muscle.

Iterations of these hill repeats, with longer climbs – say 5 to 20 minutes – in addition to blending in some neuromuscular efforts, will ultimately train the body’s intensity zones much more effectively than reactively following wheels.

Harry also discussed the importance of not going too hard, too soon with effort training, and leaving your ‘all out’ effort for special occasions, say once every 6 weeks, to see how you’re tracking.

Going too hard, too soon is a common mistake that people make when they encounter a big effort climb (probably because they’re following someone else’s wheel). They end up smashing themselves on the first major effort. From there they’ll be cooked for the remainder of the ride. This type of reactive method is an ineffective way to train.

Going to the gym on the bike

To conclude, if you’ve ever been to the gym you probably would have lifted weights. As you get stronger you increase the weight and you get to a point where you’ve identified your benchmark. You know how much you can lift and what weights you did to get there.

Training with power is no different. It enables you to lift the right weights at the right time to ensure you can get to your ultimate strength and capacity in a smart and analytical way.

Looking for a new power meter? Find power meters for sale on the Bike Chaser Marketplace